Behind the Scenes of System76: Industrial Design

Since moving into a factory space in 2018, System76 has delved deeper and deeper into manufacturing hardware in-house. Three years later, we’ve introduced five Thelio desktops, fine-tuned the hardware, developed our fully configurable Launch keyboard, and optimized our production processes. Helming the design process is Mechanical Engineer John Grano, who wears a number of different hats here. We sat down with John this week to discuss industrial design and the team behind our beautiful open source hardware.

How would you describe industrial design for people unfamiliar with the term?

To me, industrial design is basically the art of making something into a usable product. In industrial design, you have to balance looks and function, and that drives your form. It’s kind of like hardware UX in that it’s really important to have the right feel. If you can make the system connect better with people, they’ll like it more. Adding that softness we do with Thelio, like slightly rounded edges and darker wood, it makes it a little more approachable to have a semi-natural looking system and not something that’s blinking at you with red lights all the time.

System76 itself is a group of hardcore programmers and people that are really into Linux, but I think the idea of trying to democratize Linux is extremely important. If you can create something that doesn’t have that robotic aesthetic, it will provide people with something that feels more familiar and usable. No one really wants to go sit in a car that looks like a square with wheels on it. They want something that makes them feel something, maybe openness or comfort, when they’re in it.

What inspired you to get into mechanical engineering, and how did you end up at System76?

The way my brain works lends itself well to engineering, for better or for worse. There’s a lot of really solid engineers who don’t have much creativity, and then there are a lot of people who have great creative ability, but can’t do math. I kind of fluctuate in the middle; I wouldn’t say I’m the best at math or the most creative person in the entire world, but I have enough of each that the combination pushed me towards mechanical engineering. I like working with my hands, and it’s more of a study of how things work in the real world versus computer science, which is a purely digital and nontangible practice.

During school I worked mainly as a bike mechanic, and that helped me to think about how to build things better. That led me to my first internship at a bike company working in a wind tunnel, which was really fun. Realizing that I could probably never get a job there—or at least one that would pay me enough to live—I started working at an environmental engineering company, where I prototyped scientific sampling systems for R&D that would process materials with all these gasses at really high heat and tried not to die. It was kind of fun making these large-scale systems that were basically just gigantic science experiments, but I didn’t really have the creative outlet I wanted in terms of making something that looks good.

One of the main things that drew me to System76 was being able to have a solid influence on what tools we were able to use and how we were going to push the design. In the past three years, it’s pretty wild to see what we’ve been able to accomplish coming from a completely empty warehouse to being able to crank out parts.

I had also previously, while working at these scientific instrument companies, been working with a local company to design and develop a cargo bicycle, so I had that experience as well in terms of consumer product development with overseas manufacturing. I think that helped get me in the door here.

Let’s talk a bit about your team. Who do you collaborate with on a typical day?

It’s a very small team and everyone does a lot. I pretty much lead the mechanical engineering team slash design team…slash manufacturing team. Being a small company, we are all wearing a bunch of different hats. Aside from doing the initial design work on all of our Thelio desktops and the Launch keyboard, I also program our laser-punch machine and our brake press and run through all of the design for manufacturing hang ups that show up. Those changes tend to be a result of our current tools, and internal capabilities.

Crystal came on last August as our first CNC Machinist. She heads up all of the machining, trains our operators, makes sure our parts are coming out in a nice clean fashion, and has done a lot of work on minimizing machine time and maximizing the parts we can get out. She also provides really great feedback on what’s possible and what kind of special fixtures or tools we’ll need to make for a specific part. Around the same time we picked up our first Haas 3-axis CNC mill to start working on the Launch project. That led to some other opportunities to make parts for Thelio and improve the feel of some of the parts that we were pumping out.

We just hired Cary, who came from a similar background as me in consumer product development, as well as low-scale scientific machine development. He’s going to help build manufacturing tools for us, and he’s only been here now for two or three weeks. Going forward, Cary will be heading up the Thelio line long-term, and I’ll be moving to some interesting R&D work.

And Zooey?

Zooey doesn’t really do much. She just kind of sits there and waits for people to feed her their lunch. I take her out for walks during the day so she can get away from everyone petting her. She doesn’t like when they do that.

What was the R&D process like for Launch?

Launch is a less complicated product in that we don’t have to deal with things like cooling. Even dropping a PCB into aluminum housing deals with multiple processes, like using the laser and CNC machine. This was a start to looking at those processes to see how much time it takes to produce parts, the costs going into making them, and monitoring the cutting quality. You have to be familiar with the machines and know what you’re looking for when you see a tool going dull.

We first let the software experts do their thing and optimize a layout they wanted for their programming life. Then I was given that template, built a couple of sheet metal chassis that we wired up to test that layout, and made a bunch of little changes to that to get that right secret sauce for our keyboard-centric workflow in Pop!_OS. Once we got a sheet metal product that we were sure was going to be usable, we decided officially that we were going to pursue making a keyboard. That came with a whole new set of manufacturing requirements that we would have to look into.

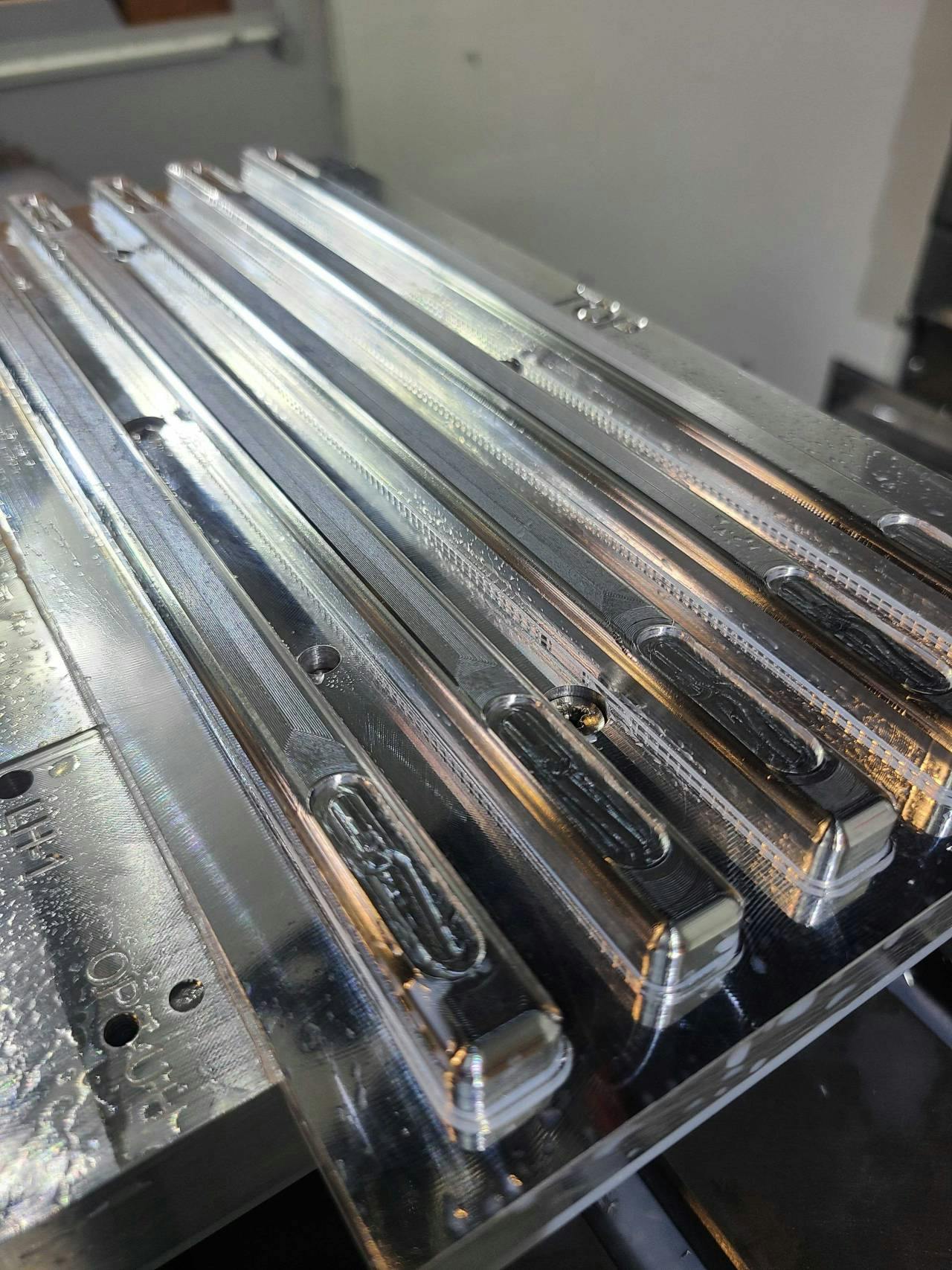

We spent a ton of time working on pocket profile. When you look at a Launch, you’ll see that it’s not a perfect rectangle. That’s because when you’re using a mill, you have a round tool, so you can go through and get close to a pretty small radius on the corner, but you can never make it exact. If we wanted to get a very small, tight pocket, we’d have to use a very small cutter that takes an extremely long period of time.

We’re taking raw billet, which are these huge 12-foot-long sticks of aluminum that we cut down to get our final product. We went with a rounded rectangle so that we could use our cutter and decrease the overall time to machine that part. There was a lot of work in that and making sure the pockets were all 13.95mm versus 13.9mm versus 14.1mm.

We also did a lot of R&D on how we go about putting the angle bar on. Magnetic assembly seemed to be a good idea. We went from trying to glue magnets in to doing what’s called press fitting. The bars come right out of powder coating while they’re nice and warm, when the aluminum is slightly larger than when it cools down. Those magnets aren’t actually adhered to anything in the bars; they’re squeezed in nice and tight from the aluminum cooling and contracting around them. That’s called a press fit, and doing that makes the process faster and less expensive.

It’s similar with the bottoms of Launch; we have steel plates that we press fit into that part as opposed to gluing or screwing, but that we do before powder coating; steel rusts, and we don’t want someone opening up their keyboard in a year and finding a little bit of rust floating underneath their super high-end PCB. So we do that, sand it down, use our media blaster to clean off the surface from the tool paths you see from the mill, and then we powder coat it through and through.

Word on the Denver streets is that Thelio Major is getting a redesign soon. What does that entail?

We’re bringing Thelio Major a lot more in line with Thelio Mega in terms of a different PCI mount for graphics cards, because we know that’s been a pain point for a lot of our users. We want to provide a little bit more robust installation for these graphics cards, which continue to increase in size and weight. The NVIDIA 3000-series cards are almost a pound heavier in some instances, and that’s a lot of weight to be shipping across the country.

We also want to continue to make Thelio Major cooler and quieter when it’s running with these new GPUs. Our new brake press allows us to make radius bends on parts, so we’re starting to run through R&D of a laser-welded external. It’s a wholesale departure from us using custom brackets and 3M VHB tape. That will provide a nicer finished product to our end user, and it’ll allow us to make our product faster with less material and less steps.

What qualities do you look for when adding someone to the team?

Creativity is extremely important. As a small manufacturing company, our priorities can shift on a day or in an afternoon where we don’t have the full line of product anymore. There are all sorts of examples in the past few years of times where you have to react pretty quickly. The motherboard’s been EOL’d, or we have to change our sheet metal design, build a new part, things like that. Making sure that someone can adapt to those changes on a moment’s notice is one of the key parts of the job.

We also want people who get excited about a new challenge and have the desire to keep improving something. I look for people who like to make things and go back in and refine it and not hold it up on this pillar. It’s good to not look at something like it’s perfect.

You have a lot of love for your Audi. What do you love about it over other options?

I like German cars. We have a family of them. They’re high-performance and not too expensive if you do all the work on it yourself. There’s a huge after-market community that tunes and changes these cars, which is pretty fun. Plus I prefer the metric system. Having a standard system drives me nuts, because what the [REDACTED] are fractions?

My real love, though, is bikes. I love tuning and riding bikes, and I love that more than I like to work on cars. It comes out of tinkering. I work with carbon fiber, I’ve done a lot of repairs on bikes over the years—there’s a certain sense of freedom you get from riding a bike that you can’t get from anything else. Not motorcycles, not cars.

Like what you see?

Share on Social Media